Should SBP be mandated to target inflation?

THE amendments in SBP act are based on a couple of assumptions. The first assumption is that a rise in interest rate can reduce inflation; therefore SBP should be given free hand to adjust the interest rate to control inflation.

The second assumption is that the government borrowing from SBP is always inflationary; therefore, government should be banned to borrow directly from SBP.

The central point in both the assumptions is price stability; therefore, a policy built on these assumptions is termed as Inflation Targeting.

The monetary policy in Pakistan is already based on these assumptions. After PTI coming into power, the benchmark interest rate known as policy rate was increased from 6% to 13.25%.

When the incumbent government took charge, the government borrowing from SBP was 5.3 trillion, making 32% of total public debt.

The government retired entire SBP debt and replaced it with the debt borrowed from commercial banks.

The motivation behind the two initiatives was to reduce inflation and these actions had their basis in the two above mentioned assumptions. But the failure of the two initiatives is no more a secret.

The inflation jumped to 12% by end of 2019 and came down to single digit only after reduction in policy rate in March 2020. Prima facie this is failure of the attempts to reduce inflation using the two policies.

On the other hands, the costs associated with the two initiatives are very huge. The mark-up on domestic debt is associated with the policy rate.

Having a debt stock of 25 trillion, a 1% increase in policy rate may lead to 250 billion increase in the mark-up payments.

Similarly, the SBP is public sector institution and mark-up earning on its lending to the government ultimately lands in government’s treasury.

The SBP’s debt was replaced with borrowing from private sector and now the mark-up on this debt will go to the commercial banks.

When the costs of a policy are so high and doubtless, the vague and doubtful benefits cannot justify the policy.

The costs of the two policies are acknowledged in the First Quarterly Report of the State of Economy published by the SBP itself.

The report confesses that ‘the steep rise in interest payments consumed over 73 percent of FBR taxes and constituted nearly 53.8 percent of total federal expenditures’ and this steep rise means the rise in policy rate.

The simple accounting on changes in domestic debt and mark-up payments between 2018 and 2019 indicates that the policy rate hike lead to additional rise of one trillion in the markup payments.

If the two assumptions were valid, the two actions aimed at reducing inflation should have brought down the inflation, but opposite happened.

At this point, a rich analysis is necessary to evaluate whether there was actually any benefit of the two actions. A project with such heavy costs cannot be left un-evaluated.

The legal framework under which the SBP is currently working, gives the mandate to SBP to evaluate the state of economy and to report it to Parliament. SBP actually presents quarterly reports to Parliament on the state of economy.

These reports evaluate everything about the economy except the monetary policy and the report carry nothing about effectiveness of monetary policy.

There is no single paper on website of SBP which provides support to effectiveness of monetary policy.

The global experience shows very clear failure of the two assumptions. All major central banks of the world responded to pandemic by reducing the interest.

If the underlying assumption of inflation targeting was valid, reduction in interest rates should lead to higher inflation, but actually the inflation reduced in all major economies of the world.

This proves that at least during the economic recessions, the reduction in interest rate doesn’t lead to higher inflation.

Similarly, all major economies of the world provided huge fiscal stimulus by borrowing from their central banks but such huge spending did not spark any inflation.

Germany provided a fiscal stimulus amounting about 35% of her GDP but there is no rise in the pattern of inflation.

Brazil reduced policy rate from 14% to 2% in three years starting from 2017, but inflation reduced continuously with the reduction in interest rate.

The average inflation during 2017 has been about 9% which has now reduced to 3% despite such a huge reduction in interest rate.

Therefore, the countries constitutionally mandated for inflation targeting have abandoned using it and started following Quantitative Easing.

All major economies except China are following Quantitative Easing which means extensive public spending and large reductions in interest rate.

But in Pakistan, an abandoned framework set to be imposed as a legal mandate of the SBP.

The resolution to the debate on inflation targeting is very simple. Practically, SBP is following inflation targeting since last 30 few years. The costs of inflation targeting are part of SBP’s quarterly reports.

Now SBP needs to present a report evaluating effectiveness of inflation targeting experience.

If SBP has something to prove the functionality of inflation targeting, the debate will come to the next question that is it worthwhile to reduce inflation by paying such a huge cost.

If SBP is having no evaluation of the effectiveness of inflation targeting, the Bank must be held accountable for the costs imposed to the government’s treasury due to its wrong policies.

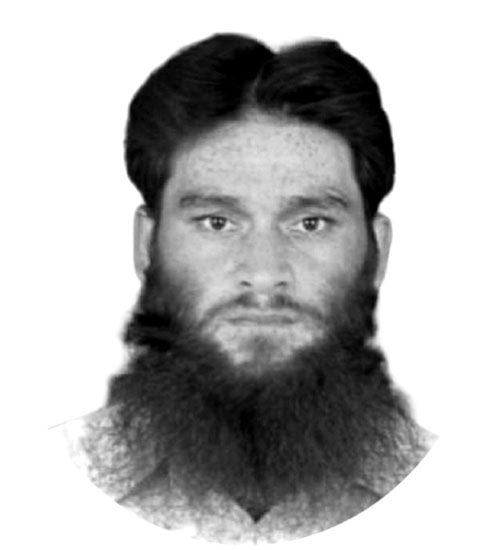

—The writer is Director, Kashmir Institute of Economics, Azad Jammu and Kashmir University.