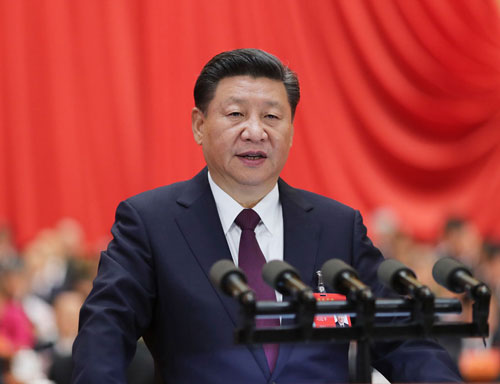

In his address at a central conference in October 2021, Chinese President Xi Jinping mentioned and elaborated on what he terms China’s “whole-process people’s democracy”.

To the untrained eye, juxtaposing democracy and communism in relation to China may seem like an anachronism. After all, “democracy” is largely associated with Western countries where people, according to the Merriam-Webster Dictionary, choose their leaders, decide on policies and programmes.

The experience and practice of China since the 1978 opening up and reform period, turns this understanding on its head and exposes its evident structural shortcomings.

Chinese democracy is markedly different from that of Western countries. Addressing the ceremony celebrating the CPC centenary, President Xi said, “On the journey ahead, we must rely closely on the people to create history. Upholding the Party’s fundamental purpose of wholeheartedly serving the people, we will stand firmly with the people, implement the Party’s mass line, respect the people’s creativity, and practice a people-centered philosophy of development. We will develop whole-process people’s democracy, safeguard social fairness and justice, and resolve the imbalances and inadequacies in development and the most pressing difficulties and problems that are of great concern to the people. In doing so, we will make more notable and substantive progress toward achieving well-rounded human development and common prosperity for all.”

What does this mean and how has it been applied and monitored regularly in the People’s Republic of China? How is its relevance most fitting given China’s rather unique history, demography, political and economic landscape?

Which lessons can be learned for South Africa as it battles to make its constitutional democracy deliver for the majority of its people, as the PRC has achieved in unparalleled quantities, in terms of the human development index (HDI) and UN’s Sustainable Development Goals (SDGs)?

Above all, whole-process people’s democracy is associated with good governance, that is, if good governance is associated with effective and efficient service delivery of common goods. Judged on this alone, the CPC has achieved this rare feat of delivering for its various citizens and diverse communities in basic and advanced education, health care, infrastructure, employment, and safety.

On this front alone, the PRC is uncompromising that public leaders must serve and prioritise national interests above selfish individual rights. The very function of Chinese state institutions is to be accountable and responsive, at all levels, to the citizens’ needs and concerns. Failure to do so is not tolerated, and there is simply no impunity for lack of effective service delivery or the perpetration of corruption and maladministration.

Let us recall that the word “governance”, using a definition from the 2015 World Public Service Report, “refers to steering”.

Steering, for example a ship, is not only a matter of keeping the ship afloat and in a forward, backward or sideways motion, most importantly, “it strongly demands knowledge of the direction and ensuring that the ship is constantly on course in that direction”.

This is not surprising since for the CPC, most prominently since 1978 and in the current trajectory under President Xi, the connection between political development, economic reform and social stability has been prized above anything else.

This has enabled the CPC to select, not holus-bolus, from other countries and their systems what works for the PRC. This selection has been cognisant of the objective material conditions in China.

Hence the role of the market economy was not left to its own devices, of pure profit-seeking, but required state facilitation to balance the wealth and income inequalities it inevitably produces.

This is a reason it is now commonplace to speak of China’s socialism with Chinese characteristics. The same is true when it comes to democracy. It has been reconfigured to respond directly to, and be applicable to, the relatively exceptional structural circumstances of China.

Unlike in other countries where the will of the people matters during electoral periods, in China the people’s interests reign supreme throughout the terms of office of public officials, from the county to president levels of administrations.

Whole-process people’s democracy is supposed to serve common interests and deliver tangible societal benefits that have, for example, enabled China to surpass, in 2019, the US as the number one source of international patent applications that were filed with the World Intellectual Property Organization.

Whole-process people’s democracy has enabled the PRC to build the world’s largest social security system and a basic medical insurance coverage which reaches more than 95 percent of the country’s population. This is in addition to the popularly known unprecedented accomplishment of lifting 770 million Chinese citizens from absolute poverty.

In the process, the CPC has reached, ahead by 10 years, the SDG Goal 1: End poverty in all its forms everywhere.

As the world battles through the Covid-19 pandemic, the PRC has shown the way with its whole-process people’s democracy just how the pandemic, in all its variants, can be handled, how to maintain economic growth, and still deliver to most citizens basic socio-economic rights. As such, Chinese democracy deserves acknowledgement for delivering on good governance that advances basic service delivery.

It is not a coincidence President Xi states simply that “democracy is not an ornament to be used for decoration; it is to be used to solve the problems people want to solve”.

We would do well to all remember that, between 2016 and 2020, the CPC created an estimated 60 million decent jobs, which is an obvious sign of Chinese democracy in action to link the attainment of socio-economic rights to the delivery of social cohesion and nation-formation.

The declaration by President Xi of China being a moderately prosperous society in all respects is related to the practice of whole-process people’s democracy.

Quite obviously, when a government is dominated by a few interest groups and mainly advances the well-being of a few and in the process the majority is excluded from benefiting from the fruits of democracy, it is an example of bad governance.

This was the conclusion of a 2014 groundbreaking study by American social scientists, Martin Gilens and Benjamin Page, that in the US it can be reasonably concluded that “economic elites and organised groups representing business interests’ impact on US government policy, while average citizens and mass-based interest groups have little or no independent influence”.

Using a South African terminology and recent experience, is this not an example of sophisticated “state capture”? From this study is it not fair to conclude that the US is more of an oligarchy than a democracy?

What are the lessons, for South Africa, that can be gleaned from China’s whole-process people’s democracy? Firstly, an executive and bureaucracy are defining features towards making democracy meaningful and having a societal impact.

When leaders simply focus on policy proclamation without emphasising implementation and even more implementation, as Singapore under Lee Kuan Yew and Rwanda under Paul Kagame have achieved, this places a risk on the sustainability of the democratic project and nation-formation programmes.

Secondly, the prosecution of those found to be implicated in acts of corruption and maladministration, by relevant law enforcement agencies, should be non-negotiable.

Thirdly, political systems should be fitting for the material conditions of a country. It does not benefit anyone to proclaim proudly that our constitutional democracy is the most “progressive” in the world when the basic needs of people are not met.

Lack of effective service delivery is the reason there are record-high incidents of service delivery protests in our country.

There is a Chinese truism that says: “A man of wisdom adapts to changes; a man of knowledge acts by circumstances”. Paul Tembe is a South African expert on China.