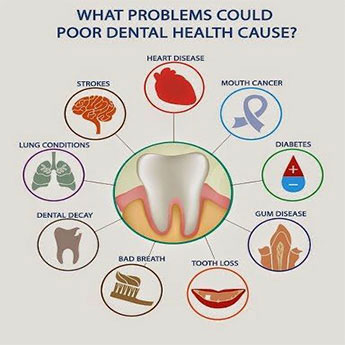

PREVIOUS research has found that poor oral health is a predictor of cardiovascular disease and mortality from all causes.

A new study suggests that having fewer remaining teeth and poor chewing ability increases the risk of muscle loss, weakness, and diabetes in older people.

Improvements in oral health, including the use of dentures — which might mitigate the risk of losing remaining teeth — could help prevent these conditions.

One of the many indirect negative impacts of the COVID-19 pandemic is that many people have been unable to see their dentists for routine care.

The strict measures implemented to prevent the spread of infection have severely reduced access to dental services. This situation led to a rapidly growing backlog of patients in need of oral treatment and care.

In the United Kingdom, for example, a survey revealed major delays in appointments for National Health Service dentistry. In response, many people have resorted to paying extra for private care.

Beyond physical discomfort, poor oral health has significant knock-on effects, including an increased risk of cardiovascular diseaseTrusted Source, research suggests.

One longitudinal study found that “oral frailty,” a measure that includes the number of remaining teeth, chewing ability, and difficulties eating and swallowing, was a risk factor for physical frailty, disability, and mortality from all causes.

A new study led by researchers at Shimane University, in Izumo, Japan, has found small but significantly increased risks of diabetes and sarcopenia, which is loss of muscle and weakness due to aging, among older adults with oral frailty.

“Although oral health might affect the overall health of an individual, it has been neglected in the public health domain,” the authors write.

The research was part of the university’s Center for Community-Based Healthcare Research and Education study, which collaborates with an annual health examination program in Ohnan, a small town in Japan’s Shimane prefecture.

To assess the participants’ chewing ability, or “masticatory function,” the researchers asked them to chew a gummy jelly as energetically as possible for 15 seconds without swallowing it, then spit out what was left.