The Indian police have launched a comprehensive “census’ to collect personal data, including details of foreign visits, from residents of Indian illegally occupied Jammu and Kashmir.

According to Kashmir Media Service, this initiative has raised concerns about its legality, possible misuse and constitutionality.

Experts are, therefore, of the opinion that the involvement of the Jammu and Kashmir Police in this census is questionable as it contradicts the existing legal framework.

While the amended census rules allow researchers access to micro-data, they stipulate that it must be anonymised and the use of sensitive and personal information must be restricted. Therefore, according to legal experts, the recent actions of the Jammu and Kashmir Police violate these legal requirements.

Residents in the Kashmir Valley have reported that police officers have been visiting households, distributing forms and asking residents to provide personal information.

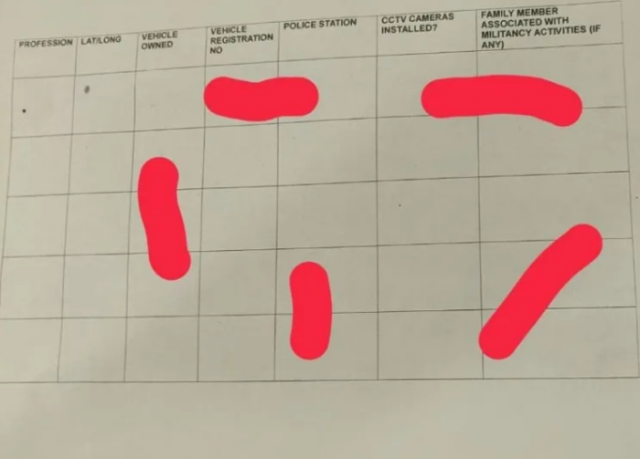

The forms distributed by the police ask for detailed information about the head of the family, family members living outside the territory, their ages, contact details, vehicle registrations, information about CCTV cameras installed and enquiries about family members. Residents must also provide photographs and the longitude and latitude coordinates (geo-tagging) of their residences.

The lack of transparency in the operation has unsettled many residents in the territory. It is still unclear under what authority this operation is being carried out and its actual purpose.

The forms, distributed by various police stations, bear the heading “Census 2024” and are labelled with the name of the respective police station or the police post. Although the forms issued by the various police stations differ slightly, the information requested from residents is standardised.

This is not the first time that such data collection initiatives have caused concern in the region. Last year, a similar “census” form distributed in Srinagar led to allegations of political profiling by security agencies.

Some residents in Jammu earlier had even taken matters into their own hands and resisted a similar “census” conducted by officials from a private agency. In November 2023, residents in a locality stopped and chased away people claiming to be officials of the Jammu Municipal Corporation. The incident was shared on social media platforms, highlighting the sensitivity of such data collection.

During the 1990s, the Indian army and the Border Security Force used to conduct door-to-door surveys to maintain a database of all households and monitor the movements of residents to gather information on militant groups.

Police set up several wings for surveillance and monitoring journalists, activists and academics. One such section, ‘Dial 100’, works on the ‘background updation’ of journalists, which includes verifying their entire professional career in the media, including their body of work, family relations, foreign travels and so on. This is, however, the first time a database of an entire population is being created by the agencies in an expansive and systemic way.

Data protection experts and civil rights activists have sharply criticised the “Census 2024”, describing it as an unconstitutional expansion of police powers and the creation of a surveillance state.

Speaking to the media, Amnesty International India Chairman, Aakar Patel, said that by demanding such information, “the Indian state is running roughshod over the rights and dignity of Kashmiris by demanding such information.”

“Unwilling to conduct a national census, the Indian government is sending out absurd and humiliating documents to families, a violation of their fundamental rights to privacy and dignity,” he said.

Renowned data protection expert, Usha Ramanathan, pointed out that the extensive data collection violates citizens’ constitutional rights to privacy.

She emphasised that the state collects personal information in unprecedented detail, enabling the creation of profiles for each individual. She drew parallels with the controversial Aadhar system, which began as a voluntary ID card programme but then became mandatory, leading to numerous problems and privacy concerns.

About the police-led census, she questioned what legitimate state objective could justify such a comprehensive measure and criticised the lack of information about the data collection and its potential use.

She argued that the operation created an intrusive surveillance mechanism that gave the state unprecedented access with 360 degrees view of each person to citizens’ lives.

“That it is being done by the police without even the minimum protections and without a mention of law under which this exercise is being conducted adds a deeply disturbing dimension to it,” she maintained.—KMS