Fahad Shah Srinagar

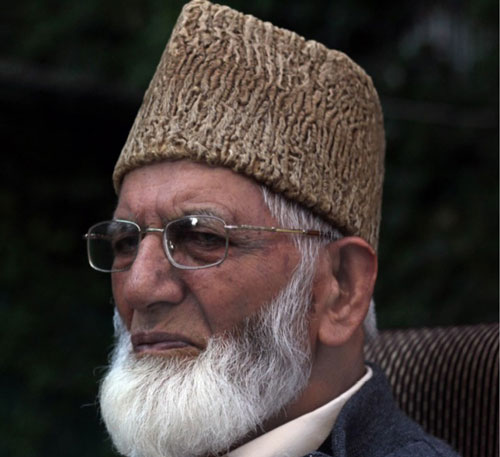

As the evening slipped into darkness on 1 Septem-ber 2021, the rumors finally came to an end. Kash-mir’s most prominent resistance leader, the 91-year-old who defied New Delhi without ever changing his stance, Syed Ali Shah Geelani was dead.

While the word spread across the villages and cities of the conflict-ridden valley, a gloom took over. With the grief of his loss, the valley was also standing on the brink of a breakpoint.

The state faced a crucial question: how to bury him without a mass funeral?

For Geelani, who had been off from the public eye in recent years, the death came in desolation. There was no mass funeral. No sloganeering. No flags. No spectacle of mourning. But a siege.

Geelani spent several years in various Indian jails after the former legislator gave up electoral politics and spearheaded the political wing of aspirations of Kashmir’s self-determination – becoming its supreme figure.For most of the last decade, he remained under house arrest.

On the intervening night of Wednesday and Thursday, a heavy contingent of government forces prevented people from reaching his home.

On Wednesday late night, by 11 pm, the gov-ernment forces were ordered to lay a siege in the valley — especially Srinagar, and turn Geelani’s neighbourhood into a fortress, guarded by more than a thousand personnel of the government forces.

Plastic barricades and concertina wire rolls were set up on the road that goes towards the Srinagar airport — and an alley on the road leads to Geelani’s resi-dence.

As journalists, including me, reached Hyder-pora, we faced the heavily armed contingent. Stand-ing outside Jamia Masjid in Hyderpora that has a patch of land as a graveyard on its right side, dozens of police vehicles passed by.

A police inspector said, “He will be buried here.” And not in the his-toric Martyr’s Graveyard, in Eidgah, as per Gee-lani’s last wish, as per his family.

A group of people were digging the grave, amid green bushes. With each passing moment, officers would walk by; one of them asked his men to bring a few more barricades as they asked us to move behind.

There were multiple points within five hun-dred meters of road where the government forces were huddled together, while dozens of their vehi-cles were parked along the road.

Journalists waited near the graveyard, trying to find a way to reach Geelani’s residence, where his body was lying, surrounded by family and a few relatives, who could reach in the dead of the night.

Two men took a coffin from the mosque, walking towards the residence. Within a few minutes, the men vanished into the darkness, along with the cof-fin.

A few residents from the neighbourhood were holding cell phones, playing videos of Geelani, browsing through social media, and seeing a photo-graph of his body.

After a while, a group of para-military forces asked us to leave further back, keep-ing us at least 500 meters away from his home.

For the next few hours, dozens of more vehicles of the government forces passed by. Convoys of senior officials went through a gap in the barricaded road, where heavily armed Special Operations Group personnel of the police stood on guard.

Pho-tojournalists could only click the shadows of the personnel, barricades, and civilians, who were barred from moving ahead on the road.

While we were waiting, a police personnel re-marked, “There were forty to fifty people at the funeral and over 150 police personnel. Now, for the next few days, we have to guard the grave.”

After waiting for hours, a few journalists, in-cluding me, attempted to reach Geelani’s residence by taking another route. Crossing a few barricades, we reached near the alley that goes towards his resi-dence. Seeping our vehicle into a few parked cars along the road, we waited quietly.

But within a few minutes, a paramilitary forces’ vehicle drove and parked next to us; after identifying ourselves, we were asked to leave, again.

Back at the spot we were earlier at, under a fly-over road, around 3:15 am, one of his family mem-bers confirmed through text message that his “body has been taken”. “Police took his body, we were not allowed to go along,” one of his grandchildren told me over the phone.

While we all waited at the same spot, back at Geelani’s home, police personnel had entered the room, where his body was kept. As per his family members, a police contingent entered inside to take his body for the burial – they refused.

“We asked them that we want to wait till morn-ing as most of our relatives have not reached yet,” one of the family members said. “They didn’t agree. They took his body away without letting anyone come along.”

In a video shared on social media, a room full of Geelani’s relatives, surround his body, wrapped in Pakistan’s flag; and women can be heard and seen screaming at a masked policeman. His grandson can also be seen speaking with the cop. “There was chaos in the room and his body was taken away,” said the relative.

With the government forces’ personnel along, Geelani was thus taken for his final rites. The fu-neral prayers were held by a local cleric and around 4:30 am, senior government officials began leaving.

The police, in its statement, said that they facilitated the family and relatives to take body from home to the graveyard.

The last rites of the revered Kashmiri leader — who once knocked a locked gate of his residence passionately, telling the government forces, who were keeping him in detention: “open this door, we won’t fly…your democracy’s funeral is being per-formed” — were finished within an hour – with a besieged burial, ending an era of Kashmir’s history.

Fahad Shah is a journalist, writer, and film-maker. He is the founder and editor of The Kashmir Walla magazine and has written extensively on politics, culture, and media in Kashmir for various national and international publications.

He was a Felix Scholar at SOAS, University of London and his first book was “Of Occupation and Resistance” – an anthology that focuses on the resistance and politics of Kashmir. In 2020, he was nominated for the RSF Press Freedom Prize for Courage.

—Courtesy: Kashmir Walla