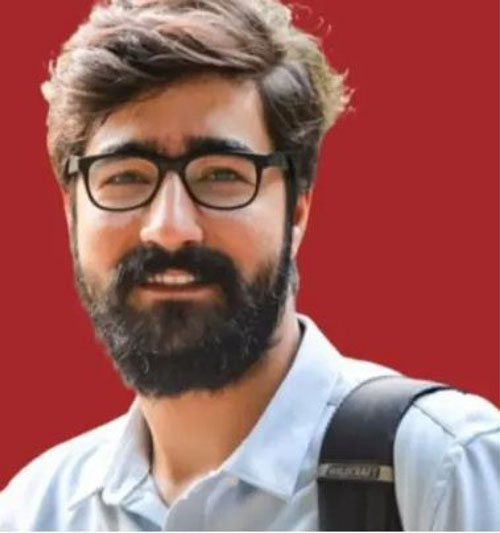

New Delhi Faced with a life threat, Kashmiri journalist Shahid Tantray spoke out about his continuing harassment by authorities in Indian illegally occupied Jammu and Kashmir (IIOJK). He sent a letter to the international and Indian press bodies and organizations seeking their help.

According to Kashmir Media Service, Tantray is a multimedia reporter for Delhi-based Caravan magazine who has recently covered important stories from the Kashmir Valley, including the crackdown on press freedom in IIOJK and Indian Army’s role in regional nationalistic protests. He is facing continued harassment by the Indian police.

Being a Kashmiri journalist, Tantray narrated his ordeal. “The officers then said I had three options in front of me. They said my first option was that I could stay in Kashmir if I gave them a written agreement that I would not write anything that goes against the government. The second option was that I could stay in Kashmir and continue writing pieces that displeased the government, in which case, they said, I would either be shot or sent to jail. They said the third option was that I leave Kashmir immediately.”

Every Kashmiri journalist’s story these days is the same. These are the only three choices they have.

Here is the text of his detailed statement released by The Caravan editorial team: Dear Sir/Madam, “I am a multimedia journalist with The Caravan in Delhi, where I have been working for nearly six years. In this time, I have reported from several states, including Gujarat, Maharashtra, and Uttar Pradesh, and on a wide variety of subjects, from communal violence to caste discrimination, to electoral politics, and the COVID-19 pandemic. In January 2022, I was in Srinagar to report stories commissioned by the editors of The Caravan, on the crackdown on journalists in Kashmir after the abrogation of Article 370, as well as the Indian Army’s presence and role in the region.

On 23 January, while I was away from home for reporting, two policemen, including a beat officer, arrived at my home. They asked my younger sister, who was alone at home, where I was. My sister was worried – she immediately phoned me and said the police had come. I asked her to give them my phone number so that they could speak to me directly. Before leaving the area, the police also asked several people in the vicinity about me and my whereabouts.

I reached home at 8 pm that day after reporting and began receiving several calls on my phone. The first call was from a sub-inspector who was posted at the Rangreth Police Post at the time. He asked me if I was the journalist Shahid Tantray and I told him I was. He asked me where I work, and I told him I work at The Caravan. He asked me several questions about my profession which I answered in a straightforward manner. After that, he told me that an official at the Sadder Police Station wanted to speak to me. I said he can share my number with the official who can call me directly. He said that since the official was his senior, he could not do that and asked me to call the official directly instead.

Over the phone, I asked the official what the problem was and why his officers were visiting my house and enquiring about me. He said there was no problem. He said that he had received a list of “prominent people” in the area from “senior officers” and was asked to enquire about them all. He said this was why he had asked the sub-inspector to call me. I asked him if this was related to the reporting I had been doing. He said it was not. I was scared that the police would pick me up and harass my family for the work I was doing, and so, for the next few days, between 23 January and 1 February, I stayed away from home, with friends. In keeping with journalistic practice, in late January, I had sent official questionnaires to the J&K police, the governor’s office, intelligence officials, as well as other government officials, for my story on the media crackdown in Kashmir.

The article on media crackdown was published on 1 February. In over ten thousand words, it extensively covered the J&K administration and the police’s attack on freedom of press in Kashmir in recent years, following the abrogation of Article 370.

For the piece, I spoke to a multitude of people, including reporters, editors, media researchers, writers and political observers. The day the piece was published, the sub-inspector called me again on the Signal application and asked me why I had published the story. He asked if there was a way for the story to be removed. I told him that reporting such stories was my job. I said I had worked on this story for over 8 months. He asked me if the story was filed to the editors before or after policemen had visited my house and questioned my sister. I told him I had filed it before that but the story was published on 1 February because The Caravan is a monthly magazine. He said okay, and cut the call.

On 3 February, the J&K police called one of my friends and asked him to inform me that I was to go to the Rangreth Police Post. I went to the Rangreth Police Post on 4 February, at around noon, along with one of my colleagues. I was made to wait outside the police station for two hours, then three police officers arrived. They were the official from Sadder police station, a deputy superintendent of police, and the sub-inspector. The first two were sitting on chairs but the sub-inspector asked me to stand to the side. After a few minutes, the deputy superintendent asked me to sit. Then, the police officials started questioning me about my piece. They asked me to tell them how I had gathered different bits of my article, and asked me to disclose my sources. The officers asked me about individual lines in this story, asking why I wrote a certain line or who a certain anonymised source in the piece was. I told them I will be unable to reveal my sources as that is against common journalistic ethics and could endanger my sources’ safety.

The deputy superintendent, who was friendly during the interaction, told me that this was a matter of “politics,” which is why they had to question me. He said, “The current situation in Kashmir is not good” and that “this was not Europe, where you can write anything.” He told me I have a long career ahead of me and should not be doing “risky work.