READING Inayat Ullah Zia’s stories one soon realizes his knack for storytelling. There is no question about his gifts as a writer as his fictional writings on Pakhtun culture and society evoke strong emotions of sorrow, joy, and wonder.

His background as a student of Pakhto literature, lifelong career at Pakistan Broadcasting Corporation, and more importantly his association with well-known scholars of Pakhto literature (eg, Qalandar Momand, Salim Raz, Hamdullah Jan Bismil, Nisar Muhammad Khan, Saadullah Jan Barq, M R Shafaq, and Aminullah Daudzai) played a significant role in honing and perfecting his craft.

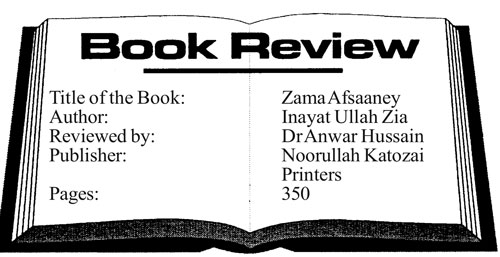

Writing reviews of fictional works is not my forte but I could not resist sharing my impressions of Zia’s perspective on life published under the title Zama Afsanay (2012), initially published as three separate books, viz, Mazegari Sori (1990), Taluna (2000) and Laywanay Pa Shesh Mahal Kay (2002).

His themes concern socioeconomic ills and inequities prevalent in Pakhtun society. Given the broad range of his themes (e.g., slow pace of economic progress, barriers to women’s realization of their dreams, ill treatment of village landless by landed, apathetic work ethic of government officials, etc.,), surely there is a little bit for everyone to enjoy and reflect upon.

His writings reveal keen awareness of his surroundings and a clear but critical insight of Pakhtun culture and society.

While he gets his inspiration from where he grew up or worked, the scenes and characters in his writings are described in a detached manner.

This was probably one of the reasons he was able to engage my attention from the get-go. I could easily relate to his characters on a personal level as well as our broader social context and shared values.

Others may feel the same way as our views are formed in ways that we are not always conscious of until alerted by someone like Zia through their writings or we encounter a different cultural perspective.

The relevance of his perspectives on life extends far beyond Pakhtun society as he frames behaviours of his characters in ways that reveal whether they conform to some higher standard of fairness or not.

While he is a proud Pakhtun, he appreciates what is good in other cultures, and does not hesitate to pinpoint any ills of Pakhtun society in his distinct satirical style.

Of the wide array of individual items in the book, most have this overarching feature that binds them in a consistent thought pattern.

This aspect of his writings is reflective of his personal life as Zia comes across as an enlightened person who holds a humanist perspective on life with an empathetic heart and respect for all human beings.

Anyone who has had the opportunity to work with him or had a discussion with him would most likely vouch for that.

Zia’s stories are often time very short which makes you wonder whether they meet any literary standards (eg, plot, setting, characters, message) for this kind of work.

I am going to leave that task to his readers to judge for themselves as making sense of any literary piece (poem, story, drama) depends not just on the writer but reader or listener as well in terms of their capacity to conceptualize and visualize ideas and relate to what the writer is trying is to convey through symbolism.

But I must say that writing short but meaning stories is not a small act, but he accomplishes it with his terse style and masterful use of literary devices (eg, similes, metaphors, proverbs).

By his distinct diction and stylistic figurative language, he makes his plots and settings vivid, inducing his readers to stay around till the end.

While Zia had ample opportunities to share his ideas with his audience via Radio broadcasts and later as published material, the full impact of his contributions would not be realized until shared with the public on a much broader scale.

As most of his writings portray abstract and symbolic characterisations of Pakhtun culture, I think television channels would serve well to extend his reach by presenting them in a dramatized way in their educational and entertainment programs.

Letting them be a part of public schools and colleges curricula would do so as well.

While they were written during 1985 through 2000, they should still be of interest to students as not much has significantly changed since then.

Regardless, we hope Zia would continue his contributions to Pashto literature and inspire us all by reminding us of the social ills that afflict Pakhtun society and the role we all have in them.

—The writer is contributing columnist, based in Peshawar.