Sultan M Hali

THE conflict in the Middle East has taken a serious turn and owing to its unique placement in the Islamic world, Pakistan is likely to get sucked into it. Pakistan’s geography too brings out her role not only in geo-politics of Middle East but also towards South and Central Asia. In this milieu, where two decades of Afghan war and nefariously planned proxy sectarian war within its borders have polarized the society, Pakistan has to tread the tight rope of governance with acrobatic agility. Any conflict within the Islamic world is perceived by the Pakistani nation through a sectarian prism which curtails its foreign policy options. So far Pakistan has bent backwards to maintain neutrality.

It refused to aid Saudi Arabia in its war in Yemen but did permit its former Army Chief, General Raheel Sharif to lead a multi-nation Arab Force. Pakistan has also refused to be sucked in the anti-Iran stance adopted by the US. For the moment, the country has successfully conveyed its message of upholding neutrality, but the challenge will become increasingly cumbersome if the ongoing US-Iran tension escalates into an all-out war. The redeeming factor is that in an election year, Donald Trump will avoid going to war. However, if push comes to shove, and seeking the plea of “Commander-in-Chiefs are not changed in time of war”, the US may plan a conflict with Iran. Such a scenario will test Pakistan and it will have to choose its options prudently.

Pakistan has a homogenous society with many ethnicities and sects living peacefully. However, due to foreign sponsored sectarian internal rifts, the nation has started to gauge each conflict in a sectarian perspective. If Muslim countries of other sects are not willing to tailor their policies as per Pakistan’s sensitivities it is illogical for us to cater to theirs. It must be remembered that Saddam, Gaddafi, Osama and Qasim Soleimani all were from different sects; however, their murderer remains one. This implies that while we may view each conflict in sectarian aspects, the world views us as Muslims only.

Despite the fact that Pakistan has invested a lot in the Middle East in pursuit of its Muslim identity and in order to gain geostrategic, diplomatic and economic support from the region, it has gained some economic advantages out of this, which may come at a political cost. Pakistan’s progress must not be made hostage to loyalties or sympathies of other nations. Recently, Prime Minister Imran Khan committed a faux pas by declining the invitation to attend the Kuala Lumpur summit — which he had himself proposed — to please Riyadh. Damage control later by visiting Malaysia and inviting the Turk President Recep Tayyip Erdogan to Islamabad may have saved us from momentary embarrassment, but Pakistan has to step carefully.

A conscious effort needs to be made by religious quarters to shun away any hatred towards members of other sects. The so-called Muslim world is not coherent in terms of social, cultural and intellectual trends — and rightly so — because it is diverse in all these terms but is affected by political developments in the Middle East. In fact, a political change in the region alerts the Muslim-majority countries and societies to its likely impact in the forms of religious radicalism and sectarian divide. It also adds weight to the argument that extremism is a political phenomenon, which feeds on religious sentiments. It is ironic that Gulf states, particularly Saudi Arabia and Iran, have deepened their political influences in Muslim societies on sectarian lines and also support their proxies there. These proxies promote the interests of these states by exploiting the sectarian sentiments of the masses. They not only divide societies along narrow religious and sectarian lines, but also promote intolerance against religious minorities and cultivate conspiratorial mindsets.

We have to be cognizant of this pitfall. Meanwhile, strict funding controls need to be exercised by the Government of Pakistan to avoid any influence of foreign narratives. We have already witnessed the outcome of unchecked foreign funding to various religious seminaries in Pakistan, which exacerbated the terror threats and the nation has had to pay a heavy toll in the war on terror. While we may welcome financial support from the Kingdom of Saudi Arabia and the United Arab Emirates because of the decrepit economic state in Pakistan, yet this cannot be at the cost of Pakistan’s sovereignty as Iran is not only our next door neighbour but shares its borders with the volatile province of Balochistan. Its sensitivities must be respected. For Pakistan, tension in the Middle East becomes more crucial not just because of its geographical position but also due to its strong military credentials. Any conflict in the region which will see Iran and Saudi Arabia on the opposing sides will definitely have a sectarian dimension, and Pakistan cannot escape the aftermath of a sectarian conflict emanating from a confrontation between Sunni—Saudi-UAE coalition– and Shia state—Iran.

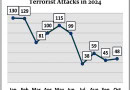

Apparently, Pakistani rulers have already started anticipating the possible security implications for Pakistan and are trying to distance themselves from the conflict as much as possible. Pakistan has acted as a conduit for the peace agreement between the US and Taliban and is trying to bring the Afghan Government and the Taliban to the negotiations table at Oslo. Meanwhile spoilers are trying to create doubts in the peace process. The Daesh targeted a gathering of Shia Hazaras in the capital, in which Dr. Abdullah Abdullah and former Afghan President Hamid Karzai escaped narrowly. Thus, the word of caution.

—The writer is retired PAF Group Captain and a TV talk show host.