Since their independence, India and Pakistan diplomatic relations have remained strained due to numerous territorial disputes. This has heavily influenced their foreign and security policies towards each other. Kashmir has remained the main point of contention, capturing widespread international attention and scrutiny. Other disputed territories like the Siachen Glacier and Sir Creek have also maintained a consistent presence in bilateral dialogue between India and Pakistan over the past three decades. Most recently, these disputes were explicitly included in the Comprehensive Bilateral Dialogue agenda agreed upon the two nations in 2015. However, the dispute over Junagadh has largely faded from public discourse despite Pakistan’s robust legal position under international law.

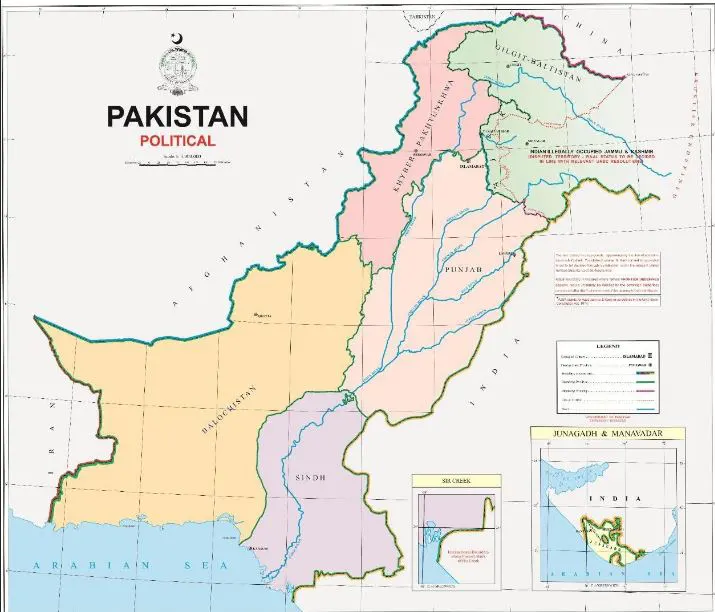

In a noteworthy development, Pakistan issued a new political map in 2020 that designates Junagadh and Manavadar as Pakistani territory, signaling an intent to bring this dispute back into focus.

Junagadh was classified as a ‘princely state’ during British colonial rule in the 19th century. It was placed under British suzerainty in 1807, with the Nawab of Junagadh retaining control over most of the territory’s affairs. At the time of independence, Junagadh had the option of either remaining independent or acceding either to the territory of Pakistan or India under the Indian Independence Act 1947. On 14 September 1947, NawabMahabat Khan of Junagadh signed an Instrument of Accession (IoA) declaring that Junagadh would be part of the Dominion of Pakistan. This was formally accepted a day later by Muhammad Ali Jinnah.This was vehemently opposed by India.

Soon after, the Indian government dispersed troops in and around Junagadh on 17 September 1947 without the consent of the Junagadh administration. Owing to surmounting pressure from Indian forces, the Dewan (Prime Minister) of Junagadh, Sir Shah Nawaz Bhutto, relinquished control over Junagadh to India on 7 November and invited India to intervene “in order to avoid bloodshed, hardship, loss of life and property and to preserve the dynasty.”The use of Indian military force to pressure the Junagadh administration to relinquish administrative control over the territory thus constituted a violation of Article 2(4) of the UN Charter.

This act of belligerence was further perpetuated through the orchestration of a plebiscite on February 20, 1948, following which India unlawfully incorporated Junagadh into its own territory. Sir Walter Monckton, the legal adviser of Mangrol, had informed Mountbatten months before the plebiscite that Pakistan’s recognition of a plebiscite was a necessary precondition. This can be likened to similarly illegal plebiscites in Russian-occupied Crimea, where over 90% ‘voted’ for annexation to Russia. Conducting plebiscite without the consent of the state that owns territorial sovereignty provides a basis for its illegality. Pakistan has not accepted the plebiscite results, claiming the territory as unlawfully occupied by India

From an international law perspective, NawabMahabat Khan had legal capacity to enter into the IoA on behalf of Junagadh. As a princely state, Junagadh operated with a considerable degree of autonomy only limited by the British Crown. The Independence of India Act 1947 differentiates between ‘dominions’ and ‘Indian States’, with the former referring to India and Pakistan. Under section 7(I)(b) of the Act, British suzerainty over princely states ended with independence of India and Pakistan, making them independent autonomous states. Consequently, it allowed these states to either operate independently or to accede to either Pakistan or India under section 2(3) of the Act, subject to the consent of the dominion being acceded to.

In Junagadh’s case, the Nawab had acted under the legal capacity and authority granted to him by the Independence of India Act 1947 and had validly executed the Instrument of Accession. Thus, as reflected by the Ministry of Law at the time, it was clear that “Junagadh’s accession to Pakistan had not been nullified by referendum and the state had not acceded to India yet.However, New Delhi went ahead because ‘it was almost likely that the referendum will be in [New Delhi’s] favour.” Nevertheless, this amounted to a unilateral decision that violated the sovereignty of Pakistan based on the IoA.

Internationally, Kashmir dispute overshadowed the issue of Junagadh. UN Security Council Resolution 47/1948 called for a plebiscite in Kashmir to decide its accession to India or Pakistan. Ayyanger had advised M.K. Vellodi, India’s representative to the UNSC at the time, on “the need ‘as far as possible to avoid being drawn into legalistic arguments as regards validity of Junagadh’s accession to Pakistan’ for its impact on Kashmir.” This shows that Indian leaders were fully cognizant of their illegal actions and did not want to bring the issue of Junagadh’s accession in the UNSC.

Overshadowed by the more high-profile Kashmir conflict, the Junagadh dispute has been relegated to the margins of Pakistan’s foreign policy agenda, receiving scant attention and resources. This has led to its political neglect, diminishing its prominence in diplomatic dialogues and international legal debates.

The issuance of a new political map by Pakistan in 2020 which significantly features Junagadh and Manavadar is a positive development since maps under international law are recognized to be the most formal evidence of a State’s intent and nature of claim over territory. Pakistan’s state practice should reflect its territorial claim by continuing to confer the status of ‘Sovereign in Exile’ upon the Nawab of Junagadh.

Besides the addition of Junagadh in the new political map, 15September should be notified as “Junagadh Day” by the government and steps should be taken to include Junagadh’s history and its legal status in the academic curriculum to create awareness regarding the issue.

With the death of Muhammad Jahangir Khanji in July 2023, it is imperative for Pakistan to promptly issue an official declaration acknowledging his successor as the legitimate heir to the Junagadh State. The new Nawab should be extended invitations for all significant State ceremonies,particularly those organized outside of Pakistan, to enhance global awareness of the Nawab’s status as Sovereign in Exile and India’s continued territorial violation.

In conclusion, Junagadh’s legal status is that it is part of Pakistan. The IoA remains as the authoritative legal source to determine the status of Junagadh’s sovereignty. Subsequent Indian actions constitute violations of various principles of international law, including the central UN Charter principle of respecting territorial integrity and political independence of states.

[Name of the Author:MohibWazir Email:mohib_khan_wazir@hotmail.com]