Bilal Hussain

When Gulzar Ahmad Dar reads the local newspaper, he isn’t interested in the news and latest events in Kashmir. He wants to know what is happening to his son, Manan Gulzar Dar.

The photojournalist, whose work has appeared in local outlets and publications such as The Guardian and the Pacific Press photo agency, was arrested October 10 as part of a conspiracy case in which India says militant groups were plotting to take action.

Ahmad Dar accompanied his son to the police station in the Batamaloo locality of Srinagar that day. But since then, the family has received few details about what has happened to Manan Dar, or a second son who was also arrested.

It was only through media reports that they know the National Investigation Agency (NIA) took Manan Dar into custody in New Delhi, more than 15 hours away by car.

“I got to know about my son’s arrest through neighbors and friends who have read the media reports,” Ahmad Dar told VOA.

Sitting in a small room in the family home in Batamaloo, filled with the sorrow of separation, Manan Dar’s mother, Fahmida, described her son as a jolly fellow and a wonderful photographer.

“I would have shown you his brilliant work. However, the mobile gadgets of family including my two sons are with the security agencies,” she told VOA.

Mass conspiracy charges Manan Dar and his younger brother — a 23-year-old college student who was arrested on October 17 — are among more than 20 people detained across Jammu and Kashmir as part of a mass conspiracy case.

When asked about the charges, Shariq Iqbal, a Delhi-based lawyer representing the journalist said, “Right now there is no individual charge against anyone. There is only a general charge.”

Manan Dar and his family have denied any involvement in the alleged conspiracy, Iqbal said.

Satish Tamta, the senior lawyer in the case, told VOA, “We are also as much in dark as you are.”

The lack of clarity for the accused and their families, who often have little idea why their relative was arrested or where they are being detained, is a problem across J&K.

Manan Dar is not a lone case of a journalist in the Kashmir valley suddenly facing serious accusations, often related to terrorism.

Kashmiri lawyer Mirza Saaib Bég told VOA that the prevailing uncertainty on what will merit a charge under the Unlawful Activities (Prevention) Act or other anti-terror laws has a direct and detrimental effect on the quality of information available to the public.

“Even in a situation where the charge is proven false, reliance on anti-terror legislation has potential to create suspicion and indifference towards the victim because the general public assumes that the person must have done something to merit being charged under a legislation as drastic as the UAPA,” said Bég.

As well as practicing law, Bég is a Weidenfeld-Hoffmann scholar at Oxford University. India’s anti-terror laws are vaguely worded and broadly designed, granting sweeping powers of detention that can extend for many months even before the matter is listed before any court, he said.

“The law fails to provide any legal safeguards that would prevent arbitrary abuse of the powers. These anti-terror legislations are so prone to abuse that one may wonder whether they have been shaped in this manner out of incompetence or out of malice,” Bég said.

Police in the Jammu and Kashmir region, and in the district where Manan Dar lives, did not respond to VOA’s emails requesting comment. The Indian embassy in Washington did not respond to a request for comment.

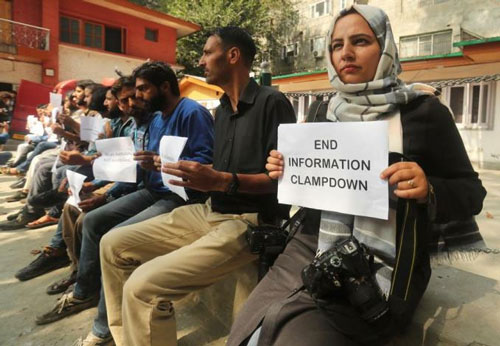

The region’s media have long come under pressure, both from regional and central Indian authorities. Since India revoked the region’s autonomy in 2019, media activists have cited a rise in arrests and harassment of journalists.

The U.N. special rapporteur on freedom of expression and the Working Group on Arbitrary Detention have also raised concerns about the “alleged arbitrary detention and intimidation of journalists covering the situation in Jammu and Kashmir.”

While the Press Council of India was in Kashmir last month to investigate conditions for the region’s press, police detained or issued summonses to five journalists, two of whom were accused of “disturbing public peace” and sent to Islamabad district jail.

The press council arranged the visit in response to a letter from Peoples Democratic Party President Mehbooba Mufti about the harassment of Kashmiri journalists.

Meenakshi Ganguly, South Asia director at Human Rights Watch, says the spate of harassment, including what she believes are politically motivated arrests of Kashmiri journalists, is extremely concerning.

“The Indian authorities have repeatedly defended their actions in Jammu and Kashmir and deny serious allegations of human rights violations, which then raises obvious questions about what they might have to hide by threatening journalists to prevent them from doing their jobs,” she said.

Ganguly described a “worrying trend in the abuse of counterterrorism and sedition laws to arrest activists and critics” and detain them for lengthy periods. “Kashmiri journalists and activists are particularly at risk,” she said.

Aasif Sultan, who worked for the monthly Kashmir Narrator, has been detained in Srinagar’s Central Jail for three years for alleged complicity in “harboring known terrorists” — a charge media rights groups believe is in retaliation for his reporting.

His detention and “other cases of arrests, detentions, interrogations and seemingly innocuous inquiries into their reports have a chilling effect on journalists,” said Geeta Seshu, co-editor of India’s free expression group the Free Speech Collective.

“If (the government) has a problem with any news reports, there are other mechanisms it could resort to. Such punitive and criminalizing action is highly condemnable,” Seshu said.

Journalists self-censor to avoid getting into trouble with the authorities or because they can’t be certain if their news outlet will back them, Seshu said.

“In Kashmir, we are seeing increasing instances of journalists being picked up for no rhyme nor reason, irrespective of whether they self-censor or not,” Seshu said.— Courtesy VOA