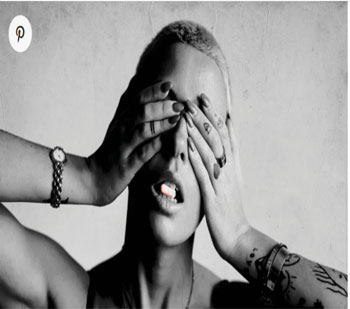

Male and female bodies are physiologically different in more than one way — from hormone levels to molecular processes. While they may feel similar levels of pain, differing underlying biological processes mean that the same treatment may not work for both. Share on PinterestPain medication does not work equally well for everyone. What role do sex-based differences play in this? Image credit: Lucas Ottone/Stocksy.

Sex and gender exist on spectrums. This article will use the terms “male,” “female,” or both to refer to sex assigned at birth. Click here to learn more.Researchers have been investigating whether males and females respond differently to pain medications for some time. A very small studyTrusted Source from 1996, for example, found that females responded more than males after receiving the opiate drug pentazocine for post-operative pain.

Much more recently, a reviewTrusted Source from 2021 noted that whilst the evidence is mixed, some studies have found ibuprofen tends to reduce pain in males more than in females.

It also reported on a study that found that prednisone, a type of corticosteroid, was associated with more intolerable adverse effects in female participants and that they were less willing to agree to a dose increase.

To understand more about how pain works differently in bodies of different sexes, Medical News Today spoke to researchers and a clinician specializing in pain.

The trouble with pain research As a starting point, MNT spoke with Dr. Meera Kirpekar, clinical assistant professor of anesthesiology, perioperative care, and pain medicine at NYU Langone, and host of a podcast on women’s health and chronic pain in women.

“Men and women don’t have heart attacks the same way, so why would anything else be the same? So there are differences in pain signals in the brain and spinal cord,” she noted.

She added that, until 2016, over 80% of pain studies have only involved male participants — whether humans or rats. Unlike males, females undergo continuous hormonal fluctuations throughout their lives that impact their pain sensitivity.

Factoring in these changes, she noted, may have been difficult in earlier research settings, ultimately leading prospective female participants to be largely left out of study cohorts.

“As a result, most pain data we have exists around male-based pain signaling. In 2016, the National Institutes of Health made it a requirement for grant applications to justify their choice of the sex of animals used in research, so female subjects began to be included in pain studies.”