Ukraine invasion and Prime Minister’s Moscow trip

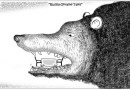

WHEN Pakistan’s Prime Minister Imran Khan said he was excited to be in Moscow just hours before Russia invaded Ukraine, he reflected the sentiment of many Pakistanis, who felt betrayed when Washington dumped its long-term Asian ally at the end of the Cold War and were jubilant at the thought of growing closer to a US rival.

When Khan made his statement, however, he was apparently unaware that Europe’s first major conflict since World War II was about to break out.

Hours later, in the early morning of 24 February, Russia attacked Ukraine, sparking a full-scale war that rages across the country.

The invasion, which was known to be imminent even before Khan left for Moscow, did not dim the Pakistani Prime Minister’s excitement about his pending meeting with President Vladimir Putin of Russia.

It was the first such parley in a decade between the top leaders of Russia and Pakistan and held the promise of beginning a new chapter in Islamabad-Moscow ties.

Back home in Pakistan, the fifth largest country in the world by population, Khan’s trip to Russia had stirred up high expectations, fuelled by his government’s billing of it as a “prelude to a greater relationship” with the country Pakistan had fought to repel in the 1980s during the war in Afghanistan.

The current rapport between Moscow and Islamabad at least in part resulted from Washington’s neglect of Pakistan.

The Muslim nation has been frantically searching for new friends ever since the Cold War ended and the United States left it out in the cold.

Pakistan’s desire to be closer to Moscow, in fact, was made public by former President Pervez Musharraf when he visited Russia in 2003.

During the Afghan war, sparked by the US invasion in 2001, Pakistan and the United States did not see eye-to-eye.

Now Washington, obviously, is unhappy with Pakistan’s failure to condemn Russia’s invasion of Ukraine.

Pakistan, on the contrary, smells a rare opportunity to reassert its position in the region as Russia seeks a greater role in Kabul, where once-despised conservative Islamic clerics now bask in the glory of defeating the world’s mightiest military.

Russia’s image as a global power would benefit if Moscow could regain a foothold in Afghanistan — the same place from which the mighty Red Army had to retreat in humiliation at the hands of the US-backed Islamic forces.

Ironically, the United States met the same fate last year when it ended its 20-year long Afghan war.

Pakistan, which was a member of the now-defunct US-led Central Treaty Organization and the Southeast Asia Treaty Organization military pacts in the 1950s to fight communism, is seeking to cash in on dramatic shifts in global power plays.

By edging closer to Moscow, it can potentially help Russia recover much of the ground it is losing in South Asia as its Soviet-era ally, India, veers more and more into the US orbit.

A reversal of the roles played by India and Pakistan, two nuclear-armed rivals, during the Cold War seems to be occurring.

Still, Pakistan is also wary of the implications of the Russian invasion for its own national interests.

Pakistan has been fighting with India over Kashmir since the 1940s.Aware of their own potential peril in Kashmir, and setting a precedent for state-to-state disagreements to be settled by force would be worrying, Pakistanis are staying neutral in the Russia-Ukraine confrontation.

They profess they favour talks over wars to resolve disputes.Nonetheless, Pakistan may derive a modicum of Schadenfreude from the United States’ impotence as Russia advances into Ukraine.

Khan had expressed his desire to work with the Biden Administration but has yet to receive a phone call from President Joe Biden, an insult hard to swallow.Putin, on the contrary, has honoured Khan with three phone calls since August.

India’s balancing act: Pakistan is far from alone in its stance, however.Other South Asian nations have shown a similar unwillingness to castigate Russia’s actions.

Even a public plea from Ukraine’s envoy to Delhi, Ambassador Igor Polikha, to Prime Minister Narenda Modi, asking Modi to personally request Putin to change course, had no effects on India.

So far, India’s public response is best summed up by External Affairs Minister S Jaishankar’s tweet on Thursday, which said he had discussed with European Union foreign policy chief Josep Borrell “the grave situation in Ukraine” and “how India could contribute to de-escalation efforts.

” India’s top diplomat pointedly refrained from even mentioning Russia, much less condemning it.

New Delhi which relies heavily on Moscow for arms and oil, views both the United States and Russia as close allies.

Siding with either one could have huge trade, defence and diplomatic ramifications.

India, however, has been inching toward the United States since the (former) Soviet Union collapsed and joined a four-member US-led anti-China coalition, along with Japan and Australia.

India’s diplomatic position reflects the national psyche: Some of the Indians are America lovers, and they want India to rebuke Russia.

But India also has many Russian romantics who expect their nation to be even-handed.Meanwhile, Moscow is pleased with Delhi’s neutral posture while Washington is decidedly not.

India’s reticence indicates its uneasiness to switch totally from Russia, its long-term military and trade partner, to its newly found friend, the United States.

Asia’s general skepticism toward the West, a legacy of European colonialism, is also at play.

On top of all this, the fateful US withdrawal from Vietnam and Afghanistan, which seriously hurt the United States’ image, have left frightening imprints on Asian minds.

—The writer is a journalist, author of “Bangladesh Liberation War, How India, US, China and the USSR Shaped the Outcome” and “The Bangladesh Military Coup and the CIA Link.

”