More than 190 countries approved a historic deal to reverse decades of environmental destruction threatening the world’s species and ecosystems at a marathon UN biodiversity summit early Monday.

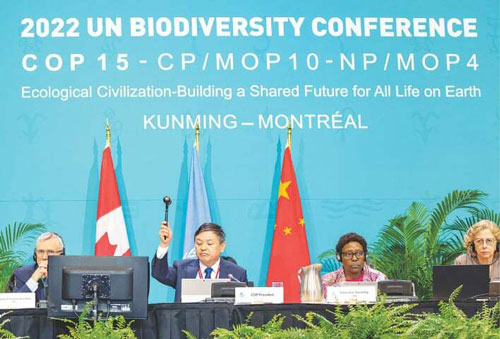

The chair of the COP15 nature summit, Chinese Environment Minister Huang Runqiu, declared the deal adopted at a plenary session in Montreal that ran into the wee hours and banged his gavel, sparking loud applause from assembled delegates.

After four years of fraught negotiations, states rallied behind the Chinese-brokered accord aimed at saving Earth’s lands, oceans and species from pollution, degradation and the climate crisis. “We have in our hands a package that I think can guide us all to work together to hold and reverse biodiversity loss, to put biodiversity on the path of recovery for the benefit of all people in the world,” Huang told the assembly.

His Canadian counterpart and host Steven Guilbeault called it a “historic step”.

President of the European Commission Ursula von der Leyen welcomed the “historic” international deal on saving the world’s biodiversity, calling it “a roadmap to protect and restore nature”. “This agreement provides a good foundation for global action on biodiversity, complementing the Paris Agreement for Climate,” she said.

However, the move overruled an objection from the Democratic Republic of Congo that had refused to back the text, demanding greater funding for developing countries as part of the accord.

Biggest conservation deal

The deal pledges to secure 30 per cent of the planet as a protected zone by 2030, stump up $30 billion in yearly conservation aid for the developing world and halt human-caused extinctions of threatened species.

Environmentalists have compared it to the landmark plan to limit global warming to 1.5C under the Paris agreement, though some warned that it did not go far enough.

Brian O’Donnell of the Campaign for Nature called it “the largest land and ocean conservation commitment in history.” “The international community has come together for a landmark global biodiversity agreement that provides some hope that the crisis facing nature is starting to get the attention it deserves,” he said.

“Moose, sea turtles, parrots, rhinos, rare ferns and ancient trees, butterflies, rays, and dolphins are among the million species that will see a significantly improved outlook for their survival and abundance if this agreement is implemented effectively.” The CEO of campaign group Avaaz, Bert Wander, cautioned: “It’s a significant step forward in the fight to protect life on Earth, but on its own it won’t be enough. Governments should listen to what science is saying and rapidly scale up ambition to protect half the Earth by 2030.”