Farzana Nisar and Humaira Nabi

Fifteen-year-old Manzoor Ali strode briskly through ankle-deep snow on his way to Kokernag on a misty February morning. Under ordinary circumstances, he would have been trudging to school. But Manzoor has been working as an assistant to a mechanic since March 2020, when schools across Kashmir closed in response to the COVID-19 pandemic, and he needed to make it to work on time.

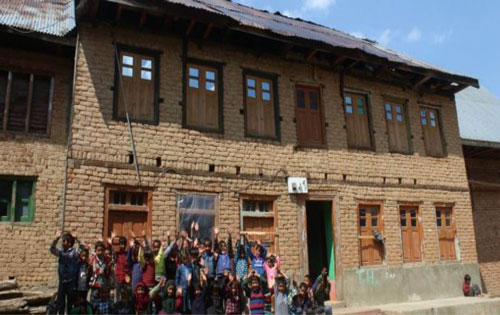

“My father is a construction labourer and could earn barely enough to sustain our family of six during the crisis. Since going to school wasn’t an option at the time, I decided to share his load,” Manzoor said. A tribal boy on his way to work in Kashmir. Photo: Special arrangment. ‘What will we choose: education or food?’

As several nations locked down at the onset of the pandemic, children across the world shifted to online learning to avoid educational losses. However, for the underprivileged children of Kashmir’s Gujjar-Bakerwal community, online education remained an elusive dream. Both smartphones and the internet were inaccessible. This digital divide, coupled with the loss of jobs during the lockdown, forced many tribal families to send their children out to work, the daily wages they earned helping to support their households.

Manzoor belongs to Nala Sund Brari village of Kokernag. He was enrolled in a local middle school, but his family couldn’t afford to buy a smartphone and in any case, internet connectivity in his village is poor.

“Survival was the biggest challenge for us during the lockdown. What is a poor man supposed to chase, education or two meals a day?” he asked, wiping grease off his hands.

For 13-year-old Munazah, education became a glaring question mark when her father lost his sole source of living. The family used to sell milk products and cornbread in central Kashmir’s Ganderbal, but the pandemic brought that to an end. Munazah’s father, Abdul Majid, struggled to ensure that his three children were able to attend online classes, but could afford only one smartphone. Gender discrimination meant that one smartphone went immediately to Munazah’s younger brother.

“While my brother and his friends climbed to a hilltop to access the internet for online classes, I was left behind doing household chores and my older sister, Sheeraza Bano, worked as a domestic helper in a nearby town,” Munazah said. “The situation was despicable.”

According to the 2011 Census, Gujjar-Bakerwal women constitute 79.7% of all the Scheduled Tribe (ST) women of Jammu and Kashmir, but lag behind in education: 82.2% of them are illiterate. The education of these underprivileged women further deteriorated amid the pandemic as the gender gap in the community’s access to technology grew wider.

The decision of the Jammu and Kashmir administration to reopen schools in March two years after they closed has rekindled hope in Munazah. “I am excited to go back to school and meet my friends,” she said with a giggle.

However, for working children like Manzoor and Sheeraza, education is a thing of the past. “I don’t feel like going back to the classroom. I can’t back off from my responsibilities now,” Manzoor told The Wire.

‘Online learning is not possible for the poor’ The long-term effects of the pandemic will likely shoot up the school dropout rate in the Gujjar-Bakarwal community of Kashmir.

According to Suhail Mehraj, a youth advocate at the UN and a tribal social worker, the abrupt shift from offline to online education did not work for these children.

“Most of the students from these communities are admitted in government-run schools. Their families cannot afford gadgets. Even the few who had the devices were unfamiliar with digital platforms and that interfered with their education,” he said.

First-generation school-goers like these children are always vulnerable dropping out of school in any case, Mehraj added. “Chances are always high that they will be trapped in various forms of work to provide for their families,” he explained.

According to data retrieved from the official website of the Ministry of Human Resource Development, Government of India, for the period between 2001-02 and 2010-11, the overall dropout percentage among children from ST communities was 60.51% a year.

“Being economically backward and illiterate, these tribal children are already at a higher risk of giving up their studies early. Their digital deficiency has further increased the gaps in their learning,” said a tribal teacher on condition of anonymity. “We expect a steep rise in the dropout rate of the community as most of these children will not find their way back to the classrooms.”

Zahid Khan, a 12-year-old shepherd boy who tends a flock of sheep near his home, a makeshift nomad hut, in Ovura village in Pahalgam, is highly unlikely to return to school. Tending sheep has been his everyday job since the pandemic struck.

A tribal boy herding his sheep in Pahalgam, Kashmir. Photo: Special arrangment.

Zahid is from a nomadic family which shifts between the lower and higher reaches of Pahalgam with the change of seasons every year. He used to attend a mobile seasonal school every summer, but owing to three successive lockdowns in Kashmir since 2019, he has missed out on learning. His father, Mushtaq Khan, is a pony-walla who takes tourists and trekkers on horse rides uphill.

“The Amarnath Yatra was cancelled the last two years due to the pandemic, so we had no income,” Mushtaq said. “I looked for ways to feed my family while my son took care of the sheep.”

Zahid misses school. He enjoyed his classes, but knows online learning is not possible for him. “Online learning is not for poor people like us,” he said. “We have one phone in our family and that too is not a touch phone. Had I continued to be in touch with my curriculum, I would never have left it. Now I will never be able to make up the lessons I have missed. It is better that I continue rearing animals and help my family eat better. I guess I am happy with what I am doing now.

—Courtesy The Wire