Shivansh Saxena

Aap khana bana kar rakho, main sabzi le aaunga Lal Chowk se,’ are surely not the last words one would want to hear from their loved ones before them disappearing into thin air.

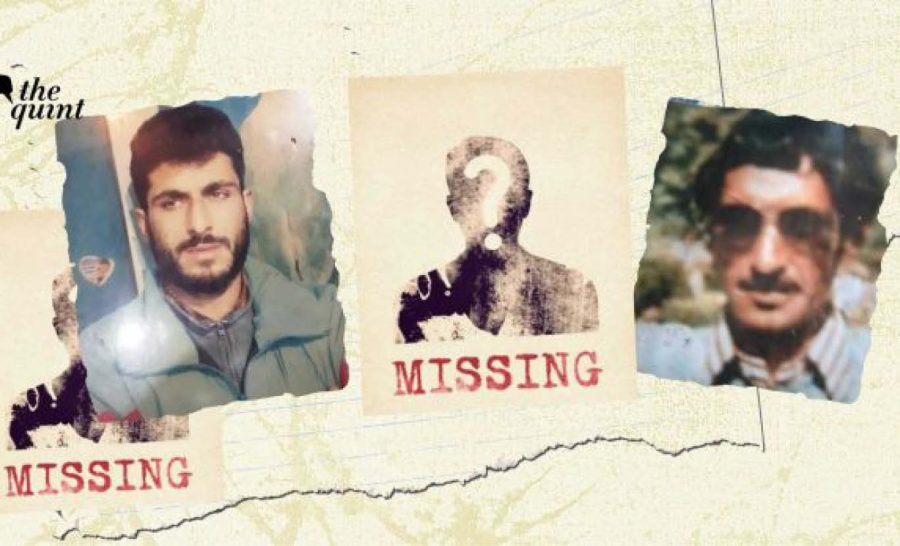

Shakeela reminisces the 1992 Lal Chowk crack-down, when Bashir Ahmed Sheikh, her father-in-law and a painter by profession went to Lal Chowk to buy some paint and vegetables but unfortunately couldn’t have that last meal.

Bashir was the sole breadwinner for his family- a wife and three sons. After the disappearance, the condition of their house has continuously deterio-rated as the schooling of the children had to be dis-continued and his wife has to learn tailoring, which brought bare minimum into the house.

Compensation System Set Up For Failure The State offers two compensations in cases of enforced disappearances:

An ex-gratia amount to the family of the miss-ing person on the condition that the person is dead and was not involved in any ‘militancy related ac-tivities’, in case the missing person returns, the amount has to be returned to the government as well; and

A job under SRO-43 to one family member.

The government only begins the investigation if the family members meet practically impassable condi-tions, such as providing the date and circumstances of the death or disappearance, as well as the location of the grave presumed to contain their loved one with some degree of certainty.

This problematic approach does not take into account people who have disappeared but are living, exacerbating the grief suffered by the family.

Bashir’s family was awarded a compensation of 1 lakh rupees in 1999 with an assurance that Shakeela’s husband would be given a job as well.

But unfortunately, that assurance didn’t come too well as the state couldn’t provide him the job but instead gave them a cheque of 4 lakh rupees in 2019 which is to be cashed in 2022 only, as told by the state.

Another one was Shabbir Hussein Bhat, who went to meet his friend but never returned.

His brother, Shafiq Ahmed Bhat, who works as a daily wage labourer now, recounts the disappearance of his brother on 27 April, 1966 when he was taken into the custody by some Army personnel.

The matter was taken to the court but the army personnel never appeared despite many summons.

They were also awarded a compensation of 1 lakh rupees in 2006 but the case still stands as it is in Jammu & Kashmir High Court.

Just like Shakeela and Shafiq, thousands of other families do not know if their family members are alive or dead.

Absence of Law

Despite the graveness of the offence of enforced disappearances, India still lacks a strong domestic legislation against it.

Several Indian and International human-rights groups have investigated the suspicious disappear-ance of Kashmiris, including European Union, Hu-man Rights Watch, and the National Human Rights Commission of India (NHRC).

The International Convention for the Protection of All Persons from Enforced Disappearance codi-fies individuals’ right to be free from enforced dis-appearances in all circumstances.

However, since India signed but did not ratify the convention, it is not entirely bound by its provisions.

However, as a signatory, India must not behave in a manner that contradicts the aim and intent of the Convention to Protect All Persons from En-forced Disappearance.

Article 33 of Additional Protocol I of the Ge-neva Convention expressly allows States to locate missing persons of the adverse group.

However, it is hard to put this duty on the Indian government be-cause in non-international armed conflicts such as Kashmir, the majority of victims of enforced disap-pearance are not foreign nationals and are accused of supporting the opposition or militancy.

AFSPA Has Rendered Seeking Justice Mean-ingless Around 8,000-10,000 civilians have been subjected to enforced disappearances in Kashmir since 1989 according to the Association of Parents of Disappeared Persons (APDP).

The Jammu and Kashmir government refuted this, claiming that all of the bodies were those of foreign militants and that the majority of the 8,000 missing had not dis-appeared but had fled to Pakistan to train as mili-tants.

The government has long been well aware that widespread killings and disappearances have oc-curred in Kashmir, but it has looked the other way.

The only recourse that an affected family has is filing a habeas corpus writ petition in the superior courts, which are not being heard expeditiously. Although, under sections 174 and 176 of the Code of Criminal Procedure, any suspicious death must be investigated by the police, and if there is any suspicion that the police are at fault, an inquest must be held by a magistrate.

On the rare occasion that a missing person is lo-cated, the armed forces personnel responsible are exempt from prosecution by the Armed Forces (Jammu and Kashmir) Special Powers Act, 1990 (AFSPA).

This Act has rendered the redressal proc-ess ineffective and has failed to maintain law & order, undermining India’s ability to fulfil its obligation to guarantee access to justice.

Bring Back Our Man Or His Corpse

All the affected families echoed one thing, ‘Ya to hume laash dikhao ya aadmi’, the commonality in all the cases has been the disastrous aftermath of the family and the charges of custody were never com-municated to the family till date.

Both Shakeela and Shafiq lost two other family members apart from the missing person while chas-ing the government for justice with little to no re-sources.

APDP has been the only helping hand for these families, Sabia, who herself is a victim of this sys-tem, continues to help those affected selflessly and empathetically.

Government of India needs to remove these obstacles which provide impunity to the security forces under Armed Forces (Special Powers) Act (Section 7), the Disturbed Areas Act (Section 6) and the Code of Criminal Procedure (Section 197). All culpable individuals and entities must be held ac-countable.

It is high time that the Kashmiri demand for a fair investigation into the fate of missing persons be investigated and a legislation be enacted to recog-nise enforced disappearances for what they are — a heinous, dastardly crime.

(Shivansh Saxena is a law student based out of Delhi. He is passionate about civil liberties and public policy. He’s also a member of Indian Civil Liberties Union)

—Courtesy The Quint